Skillnad mellan versioner av "Potenser"

Taifun (Diskussion | bidrag) m |

Taifun (Diskussion | bidrag) m |

||

| Rad 1: | Rad 1: | ||

{| border="0" cellspacing="0" cellpadding="0" height="30" width="100%" | {| border="0" cellspacing="0" cellpadding="0" height="30" width="100%" | ||

| style="border-bottom:1px solid #797979" width="5px" | | | style="border-bottom:1px solid #797979" width="5px" | | ||

| − | {{Not selected tab|[[1.1 Polynom|<-- | + | {{Not selected tab|[[1.1 Polynom|<-- Till Polynom]]}} |

{{Selected tab|[[Potenser|Genomgång]]}} | {{Selected tab|[[Potenser|Genomgång]]}} | ||

{{Not selected tab|[[Övningar till Potenser|Övningar]]}} | {{Not selected tab|[[Övningar till Potenser|Övningar]]}} | ||

| Rad 8: | Rad 8: | ||

| − | <!-- [[ | + | __NOTOC__ <!-- __TOC__ --> |

| + | == <b><span style="color:#931136">Vad är en potens?</span></b> == | ||

| + | <div class="exempel"> | ||

| + | [[Image: Hur raknar du Potenser 20.jpg]] | ||

| + | :<math> {\rm {\color{Red} {OBS!\quad Vanligt\,fel:}}} \quad\; 2\,^3 \; = \; 6 </math> | ||

| − | + | :<math> \qquad\quad\;\, {\rm Rätt:} \qquad\qquad\! 2\,^3 \; = \; 2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 \; = \; 4 \cdot 2 \; = \; 8 </math> | |

| + | </div> <!-- exempel --> | ||

| + | <div class="tolv"> <!-- tolv1 --> | ||

| + | Felet beror på att man blandar ihop två olika räkneoperationer: multiplikationen med <strong><span style="color:red">upphöjt till</span></strong>. | ||

| − | + | Hjärnan associerar <math> \, 2 \, </math> och <math> \, 3 \, </math> blind till multiplikationstabellen vilket ger <math> \, 6 \, </math>. | |

| − | + | I själva verket betyder <math> \, 2\,^{\color{Red} 3} \, </math> inte <math> \, 2 \cdot 3 \, </math> utan <math> \, \underbrace{2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2}_{{\color{Red} 3}\;\times} \, </math> och är en: | |

| + | </div> <!-- tolv1 --> | ||

| − | + | <table> | |

| + | <tr> | ||

| + | <td><div class="border-divblue"><big> | ||

| + | <b>Potens</b> | ||

| − | ::<math> | + | ::<math> 2\,^{\color{Red} 3} \; = \;\; \underbrace{2 \, \cdot \, 2 \, \cdot \, 2}_{{\color{Red} 3}\;\times} </math> |

| − | + | <b>Upprepad multiplikation av </b> | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | <b><math>2 \, </math> med sig själv, <math> \, {\color{Red} 3} \, </math> gånger.</b> | |

| + | </big></div> | ||

| + | </td> | ||

| + | <td> [[Image: Potens Bas Exponent_80.jpg]]</td> | ||

| + | </tr> | ||

| + | </table> | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | <div class="tolv"> <!-- tolv2 --> | |

| + | <math> \, 2\,^3 \, </math> läses <math> \, {\color{Red} 2} </math> <strong><span style="color:red">upphöjt till</span></strong><math> \, {\color{Red} 3} \, </math> och kallas för <strong><span style="color:red">potens</span></strong>. <math> \, 2\, </math> heter <strong><span style="color:red">basen</span></strong> och <math> \, 3 \, </math> <strong><span style="color:red">exponenten</span></strong>. | ||

| − | + | Exponenten <math> \, {\color{Red} 3} \, </math> är inget tal i vanlig bemärkelse utan endast en information om att <math> \, 2 \, </math> ska multipliceras <math> \, {\color{Red} 3} \, </math> gånger med sig själv (jfr. [[1.2_Räkneordning#Varf.C3.B6r_g.C3.A5r_multiplikation_f.C3.B6re_addition.3F|<strong><span style="color:blue">upprepad addition</span></strong>]]). | |

| + | </div> <!-- tolv2 --> | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | <div class="exempel"> <!-- exempel1 --> | |

| + | == <b><span style="color:#931136">Exempel 1</span></b> == | ||

| + | <big> | ||

| + | Förenkla<span style="color:black">:</span> <math> \qquad \displaystyle{2\,^3 \cdot \; 2\,^5 \over 2\,^4} </math> | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | <strong><span style="color:#931136">Lösning:</span></strong> <math> \qquad \displaystyle{{2\,^3 \cdot \; 2\,^5 \over 2\,^4} \, = \, {2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 \quad \cdot \quad 2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 \over 2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2} \, = \, {2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 \quad \cdot \quad 2 \cdot \cancel{2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2} \over \cancel{2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2}} \, = \, 2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 \, = \, 4 \cdot 4 \, = \, 16} </math> | |

| + | :::::::::::::::::OBS! Förenkla alltid först, räkna sedan! | ||

| − | == | + | Snabbare<span style="color:black">:</span> <math> \qquad\!\! \displaystyle{{2\,^3 \cdot \; 2\,^5 \over 2\,^4} \, = \, 2\,^{3\,+\,5\,-\,4} \, = \, 2\,^4 \, = \, 2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 \, = \, 4 \cdot 4 \, = \, 16} </math> |

| + | </big> | ||

| + | </div> <!-- exempel1 --> | ||

| − | |||

| − | [[ | + | <div class="tolv"> <!-- tolv2 --> |

| + | För att förstå den snabbare lösningen se [[Potenser#Potenslagarna|<strong><span style="color:blue">potenslagarna</span></strong>]]. | ||

| + | </div> <!-- tolv2 --> | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | == <b><span style="color:#931136">Potens med positiva heltalsexponenter</span></b> == | |

| + | <div class="tolv"> <!-- tolv1 --> | ||

| − | + | Potensen <big><math> \, a\,^{\color{Red} x} \, </math></big> kan, om exponenten <math> \, {\color{Red} x} \, </math> är ett positivt heltal och basen <big><math> \, a \, </math></big> ett tal <math> \neq 0 </math>, definieras som | |

| − | ''' | + | ::::::<b>Upprepad multiplikation av <big><math> \, a \, </math></big> med sig själv, <math> \, {\color{Red} x} \, </math> gånger:</b> |

| + | |||

| + | ::::::::<big><math> a\,^{\color{Red} x} = \underbrace{a \cdot a \cdot a \cdot \quad \ \cdots \quad \cdot a}_{{\color{Red} x}\;{\rm gånger}} </math></big> | ||

| + | </div> <!-- tolv1 --> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div class="exempel"> <!-- exempel2 --> | ||

| + | == <b><span style="color:#931136">Exempel 2</span></b> == | ||

| + | <big> | ||

| + | Förenkla<span style="color:black">:</span> <big><math> \quad\;\; a\,^2 \, \cdot \, a\,^3 </math></big> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | <strong><span style="color:#931136">Lösning:</span></strong> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ::::<big><math> a\,^2 \cdot a\,^3 \; = \; \underbrace{a \cdot a}_{2\;\times} \; \cdot \; \underbrace{a \cdot a \cdot a}_{3\;\times} \; = \; \underbrace{a \cdot a \cdot a \cdot a \cdot a}_{{\color{Red} 5}\;\times} \; = \; a\,^{\color{Red} 5}</math></big> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Snabbare: | ||

| + | |||

| + | ::::<big><math> a\,^2 \cdot a\,^3 \; = \; a\,^{2\,+\,3} = \; a\,^{\color{Red} 5} </math></big> | ||

| + | </big> | ||

| + | </div> <!-- exempel2 --> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | <div class="tolv"> <!-- tolv2 --> | ||

| + | Den snabbare lösningen är ett exempel på den första potenslagen: | ||

| + | </div> <!-- tolv2 --> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | == <b><span style="color:#931136">Potenslagarna</span></b> == | ||

| + | <div class="tolv"> <!-- tolv3 --> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Följande lagar gäller för potenser där basen <math> a\, </math> är ett tal <math> \neq 0 </math>, exponenterna <math> \, x \, </math> och <math> \, y \, </math> godtyckliga tal och <math> m,\,n </math> heltal (<math> n\neq 0 </math>): | ||

| + | </div> <!-- tolv3 --> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | <div class="border-divblue"><big> | ||

| + | <b><span style="color:#931136">Första potenslagen:</span></b> <big><math> \qquad\qquad\quad\;\, a^x \cdot a^y \; = \; a\,^{x \, + \, y} \qquad\qquad </math></big> | ||

| + | ---- | ||

| + | <b><span style="color:#931136">Andra potenslagen:</span></b> <big><math> \qquad\qquad\qquad\quad \displaystyle {a^x \over a^y} \; = \; a\,^{x \, - \, y} \qquad\qquad </math></big> | ||

| + | ---- | ||

| + | <b><span style="color:#931136">Tredje potenslagen:</span></b> <big><math> \qquad\qquad\qquad \displaystyle {(a^x)^y} \; = \; a\,^{x \, \cdot \, y} \qquad\qquad </math></big> | ||

| + | ---- | ||

| + | <b><span style="color:#931136">Lagen om nollte potens:</span></b> <big><math> \qquad\qquad\qquad\! a\,^0 \; = \; 1 \qquad\qquad </math></big> | ||

| + | ---- | ||

| + | <b><span style="color:#931136">Lagen om negativ exponent:</span></b> <big><math> \qquad\qquad a\,^{-x} \; = \; \displaystyle {1 \over a\,^x} \qquad\qquad </math></big> | ||

| + | ---- | ||

| + | <b><span style="color:#931136">Lagen om rationell exponent:</span></b> <big><math> \qquad\qquad a^{m \over n} \; = \; \sqrt[n]{a^m} \qquad\qquad </math></big> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <b><span style="color:#931136">Specialfall <small><math>m=1</math></small> (högre rötter):</span></b> <big><math> \qquad\quad\;\, a^{1 \over n} \; = \; \sqrt[n]{a} \qquad\qquad </math></big> | ||

| + | ---- | ||

| + | <b><span style="color:#931136">Potens av en produkt:</span></b> <big><math> \qquad\qquad\;\;\, (a \cdot b)\,^x \; = \; a\,^x \cdot b\,^x \qquad\qquad </math></big> | ||

| + | ---- | ||

| + | <b><span style="color:#931136">Potens av en kvot:</span></b> <big><math> \qquad\qquad\qquad \left(\displaystyle {a \over b}\right)^x \; = \; \displaystyle {a\,^x \over b\,^x} \qquad\qquad </math></big> | ||

| + | </big></div> <!-- border-divblue --> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | <div class="tolv"> <!-- tolv3a --> | ||

| + | För enkelhets skull definierades potensbegreppet inledningsvis endast för positiva heltalsexponenter <math> \, x \, </math> och <math> \, y </math>. Men potenslagarna gäller även för negativa och [[Potenser#Potenser_med_rationella_exponenter|<strong><span style="color:blue">rationella exponenter</span></strong>]]. I formuleringen "negativ exponent" antas <math> \, x > 0 </math>. | ||

| + | </div> <!-- tolv3a --> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | == <b><span style="color:#931136">Bevis(idéer) och exempel för några potenslagar</span></b> == | ||

| + | <div class="tolv"> <!-- tolv4 --> | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Påstående (Första potenslagen)''': | ||

| + | |||

| + | ::::<big><math> a\,^x \cdot a\,^y \; = \; a\,^{x \, + \, y} </math></big> | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Bevisidé''': | ||

Påståendet kan bevisas genom att använda potensens definition: | Påståendet kan bevisas genom att använda potensens definition: | ||

| − | + | ::::<big><math> a\,^{\color{Red} x} \cdot a\,^{\color{Red} y} \; = \; \underbrace{a \cdot a \cdot \; \ \cdots \; \cdot a}_{{\color{Red} x}\;\times} \; \cdot \; \underbrace{a \cdot a \cdot \; \ \cdots \; \cdot a}_{{\color{Red} y}\;\times} \; = \; \underbrace{a \cdot a \cdot \; \ \cdots \; \cdot a}_{{\color{Red} {x\,+\,y}}\;\times} \; = \; a\,^{{\color{Red} {x\,+\,y}}} </math></big> | |

---- | ---- | ||

| − | |||

| − | :::::<math> a^0 \; = \; 1 </math> | + | '''Påstående (Andra potenslagen)''': |

| + | |||

| + | ::::<big><math> \displaystyle {a\,^x \over a\,^y} \; = \; a\,^{x \, - \, y} </math></big> | ||

| + | </div> <!-- tolv1 --> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | <div class="exempel"> <!-- exempel3 --> | ||

| + | == <b><span style="color:#931136">Exempel 3</span></b> == | ||

| + | <big> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ::::<big><math> \displaystyle {a\,^{\color{Red} 5} \over a\,^{\color{Red} 3}} \; = \; {a \cdot a \cdot a \cdot a \cdot a \; \over \; a \cdot a \cdot a} \; = \; {a \cdot a \cdot \cancel{a \cdot a \cdot a} \; \over \; \cancel{a \cdot a \cdot a}} \; = \; a \cdot a \; = \; a\,^2 </math></big> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Snabbare med andra potenslagen: | ||

| + | |||

| + | ::::<big><math> \displaystyle {a\,^{\color{Red} 5} \over a\,^{\color{Red} 3}} \; = \; a\,^{{\color{Red} {5\,-\,3}}} \; = \; a\,^2 </math></big> | ||

| + | </big> | ||

| + | </div> <!-- exempel3 --> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | <div class="tolv"> <!-- tolv2 --> | ||

| + | '''Påstående (Lagen om nollte potens)''': | ||

| + | |||

| + | ::::<big><math> a^0 \; = \; 1 </math></big> | ||

'''Bevis''': | '''Bevis''': | ||

| − | Påståendet kan bevisas genom att använda potenslagen | + | Påståendet kan bevisas genom att använda andra potenslagen: |

| − | + | ::::<big><math> \displaystyle{a^x \over a^x} \; = \; a^{x-x} \; = \; a^0 </math></big> | |

| − | ---- | + | Å andra sidan vet vi att ett bråk med samma täljare som nämnare har värdet <math> \, 1 </math>: |

| + | |||

| + | ::::<big><math> \displaystyle{a^x \over a^x} \; = \; 1 </math></big> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Av raderna ovan följer påståendet: | ||

| + | |||

| + | ::::<big><math> a^0 \; = \; 1 </math></big> | ||

| + | </div> <!-- tolv4 --> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | == <b><span style="color:#931136">Potenser med negativa exponenter</span></b> == | ||

| + | <div class="tolv"> <!-- tolv4a --> | ||

| − | '''Påstående ( | + | '''Påstående (Lagen om negativ exponent, <math> \, x > 0 </math>)''': |

| − | + | ::::<big><math> a^{-x} = \displaystyle{1 \over a^x} </math></big> | |

'''Bevis''': | '''Bevis''': | ||

| − | Påståendet kan bevisas genom att använda den ovan bevisade lagen | + | Påståendet kan bevisas genom att använda den ovan bevisade lagen om nollte potensen (baklänges) samt andra potenslagen: |

| − | + | ::::<big><math> \displaystyle{1 \over a^x} \; = \; \displaystyle{a^0 \over a^x} \; = \; a^{0-x} \; = \; a^{-x} </math></big> | |

Vi får påståendet, fast baklänges. | Vi får påståendet, fast baklänges. | ||

| + | </div> <!-- tolv4a --> | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | <div class="exempel"> <!-- exempel4 --> | |

| + | == <b><span style="color:#931136">Exempel på potenser med negativa exponenter</span></b> == | ||

| + | <big> | ||

| − | ::::<math> a^{- | + | ::::<big><math> \displaystyle{a^{-1} \, = \, {1 \over a^1} \, = \, {1 \over a}} </math></big> |

| − | |||

| − | + | ::::<big><math> \displaystyle{a^{-2} \, = \, {1 \over a^2} \, = \, {1 \over a \cdot a}} </math></big> | |

| − | |||

| − | ---- | + | ::::<big><math> \displaystyle{a^{-3} \, = \, {1 \over a^3} \, = \, {1 \over a \cdot a \cdot a}} </math></big> |

| + | </big> | ||

| + | </div> <!-- exempel4 --> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | <div class="tolv"> <!-- tolv5 --> | ||

| + | Att potenser med negativa exponenter är en naturlig fortsättning på potenser med positiva exponenter med nollte potensen däremellan illustrerar följande exempel: | ||

| + | </div> <!-- tolv5 --> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | <div class="exempel"> <!-- exempel4 --> | ||

| + | == <b><span style="color:#931136">Varför är <math> \; 5\,^0 \, = \, 1 \; </math>?</span></b> == | ||

| + | <big> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ::::<math> \;\; 5^4 \; = \; {\color{Red} 1} \cdot 5 \cdot 5 \cdot 5 \cdot 5 </math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ::::<math> \;\; 5^3 \; = \; {\color{Red} 1} \cdot 5 \cdot 5 \cdot 5 </math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ::::<math> \;\; 5^2 \; = \; {\color{Red} 1} \cdot 5 \cdot 5 </math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ::::<math> \;\; 5^1 \; = \; {\color{Red} 1} \cdot 5 </math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ::::<math> \;\; {\color{Red} {5^0 \; = \; 1}} </math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ::::<math> \;\; 5^{-1} \; = \; \displaystyle{{\color{Red} 1} \over 5} </math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ::::<math> \;\; 5^{-2} \; = \; \displaystyle{{\color{Red} 1} \over 5 \cdot 5} </math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ::::<math> \;\; 5^{-3} \; = \; \displaystyle{{\color{Red} 1} \over 5 \cdot 5 \cdot 5} </math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ::::<math> \;\; 5^{-4} \; = \; \displaystyle{{\color{Red} 1} \over 5 \cdot 5 \cdot 5 \cdot 5 } </math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Att <math> \; {\color{Red} 1} </math>-orna följer med hela tiden beror på att multiplikationens ''enhet'' är <math> \, {\color{Red} 1} </math>, dvs <math> \, a \cdot {\color{Red} 1} \, = \, a </math>. Därför blir endast <math> \, {\color{Red} 1} \, </math> kvar, när vi kommer till <math> \, {\color{Red} {5^0}} \, </math> då alla <math> \, 5</math>-or har försvunnit. | ||

| + | </big> | ||

| + | </div> <!-- exempel4 --> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | <div class="tolv"> <!-- tolv5 --> | ||

| + | Jämför med: | ||

| + | </div> <!-- tolv5 --> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | <div class="exempel"> <!-- exempel5 --> | ||

| + | == <b><span style="color:#931136">Varför är <math> \; 5 \cdot 0 \, = \, 0 \; </math>?</span></b> == | ||

| + | <big> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ::::<math> \;\; 5 \cdot 4 \; = \; {\color{Red} 0} + 5 + 5 + 5 + 5 </math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ::::<math> \;\; 5 \cdot 3 \; = \; {\color{Red} 0} + 5 + 5 + 5 </math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ::::<math> \;\; 5 \cdot 2 \; = \; {\color{Red} 0} + 5 + 5 </math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ::::<math> \;\; 5 \cdot 1 \; = \; {\color{Red} 0} + 5 </math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ::::<math> \;\; {\color{Red} {5 \cdot 0 \; = \; 0}} </math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ::::<math> \;\; 5 \cdot (-1) \; = \; {\color{Red} 0} - 5 </math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ::::<math> \;\; 5 \cdot (-2) \; = \; {\color{Red} 0} - 5 - 5 </math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ::::<math> \;\; 5 \cdot (-3) \; = \; {\color{Red} 0} - 5 - 5 - 5 </math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ::::<math> \;\; 5 \cdot (-4) \; = \; {\color{Red} 0} - 5 - 5 - 5 - 5 </math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Att <math> \; {\color{Red} 0} </math>-orna följer med hela tiden beror på att additionens ''enhet'' är <math> \, {\color{Red} 0} </math>, dvs <math> \, a + {\color{Red} 0} \, = \, a </math>. Därför blir endast <math> \, {\color{Red} 0} \, </math> kvar, när vi kommer till <math> \, {\color{Red} {5 \cdot 0}} \, </math> då alla <math> \, 5</math>-or har försvunnit. | ||

| + | </big> | ||

| + | </div> <!-- exempel5 --> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | == <b><span style="color:#931136">Potenser med rationella exponenter</span></b> == | ||

| + | <div class="tolv"> <!-- tolv6 --> | ||

| + | Potenser med exponenter som är [[1.1_Om_tal#Olika_typer_av_tal|rationella tal]] (bråktal) kan användas för att beräkna (högre) rötter. | ||

| + | |||

| − | '''Påstående ( | + | '''Påstående (högre rötter)''': |

| − | ::: | + | :::<big><math> a^{1 \over n} \; = \; \sqrt[n]{a} \; </math></big> <math> , \qquad n\neq 0 </math> |

'''Bevisidé''': | '''Bevisidé''': | ||

| − | Vi tar specialfallet | + | Vi tar specialfallet <math> n=3 </math>, multiplicerar <math> a </math><big><math>^{1 \over 3} </math></big> tre gånger med sig själv och använder potenslagen om produkt av potenser med samma bas: |

| − | ::: | + | :::<big><math> \displaystyle a^{1 \over 3} \cdot a^{1 \over 3} \cdot a^{1 \over 3} \; = \; a^{{1 \over 3} + {1 \over 3} + {1 \over 3}} \; = \; a^{3 \over 3} \; = \; a^1 \; = \; a </math></big> |

| − | Definitionen för 3:e roten ur <math> a </math> är: | + | Definitionen för 3:e roten ur <math> a </math> är<span style="color:black">:</span> |

| − | + | <big><math> \qquad\quad \displaystyle \sqrt[3]{a} \; = \; </math></big> Tal som 3 gånger multiplicerat med sig själv ger <math> a </math>. | |

| − | Men enligt ovan är det tal som 3 gånger med sig själv ger <math> a </math>, just <math> a </math | + | Men enligt ovan är det tal som 3 gånger med sig själv ger <math> a </math>, just <math> a </math> <big><math>^{1 \over 3} </math></big>. Alltså måste detta tal vara lika med 3:e roten ur <math> a </math>: |

| − | ::: | + | :::<big><math> \displaystyle a^{1 \over 3} \; = \; \sqrt[3]{a} </math></big> |

| − | Denna bevisidé kan vidareutvecklas till det allmänna fallet för alla heltal <math> m\, </math> och <math> n\neq 0 </math> | + | Denna bevisidé kan vidareutvecklas till det allmänna fallet för alla heltal <math> m\, </math> och <math> n\neq 0 \, </math> '''(Lagen om rationell exponent)''': |

| + | :::<big><math> a^{m \over n} \; = \; \sqrt[n]{a^m} </math></big> | ||

| + | </div> <!-- tolv6 --> | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | == <b><span style="color:#931136">Potensekvationer</span></b> == | |

| + | <div class="tolv"> <!-- tolv7 --> | ||

| − | + | Anta i fortsättningen att <math> \, x \, </math> är en okänd variabel och <math> b\, </math> och <math> c\, </math> givna konstanter <math> \neq 0 </math> . | |

| − | :: | + | ::Funktioner av typ <math> y = x^3\, </math> kallas <strong><span style="color:red">potensfunktioner</span></strong>, generellt <math> \; y = c \cdot x^b\, </math>. |

| − | I potensfunktioner och -ekvationer förekommer x i basen. Potensekvationer löses genom <strong><span style="color:red">rotdragning</span></strong>. För t.ex. potensekvationen <math> x^3\, = 8 </math> finns det två olika sätt att beskriva lösningen via rotdragning: | + | ::Ekvationer av typ <math> x^3\, = 8 </math> kallas <strong><span style="color:red">potensekvationer</span></strong>, generellt <math> \; x^b\, = c </math>. |

| + | |||

| + | I potensfunktioner och -ekvationer förekommer <math> \, x \, </math> i basen. Potensekvationer löses genom <strong><span style="color:red">rotdragning</span></strong>. För t.ex. potensekvationen <math> x^3\, = 8 </math> finns det två olika sätt att beskriva lösningen via rotdragning: | ||

:::<math>\begin{align} x^3 & = 8 \qquad & | \; \sqrt[3]{\;\;} \\ | :::<math>\begin{align} x^3 & = 8 \qquad & | \; \sqrt[3]{\;\;} \\ | ||

| Rad 135: | Rad 331: | ||

\end{align}</math> | \end{align}</math> | ||

| − | Alternativt (med | + | Alternativt (med rationell exponent): |

:::<math>\begin{align} x^3 & = 8 \qquad & | \; (\;\;\;)^{1 \over 3} \; \text{samma som} \; \sqrt[3]{\;\;} \\ | :::<math>\begin{align} x^3 & = 8 \qquad & | \; (\;\;\;)^{1 \over 3} \; \text{samma som} \; \sqrt[3]{\;\;} \\ | ||

| Rad 143: | Rad 339: | ||

\end{align}</math> | \end{align}</math> | ||

| − | Det alternativa sättet att lösa ekvationen | + | Det alternativa sättet att lösa ekvationen ovan visar att rötter även kan uppfattas och skrivas som [[Potenser#Potenser_med_rationella_exponenter|<strong><span style="color:blue">potenser med rationella exponenter</span></strong>]]. |

| + | </div> <!-- tolv7 --> | ||

| Rad 158: | Rad 355: | ||

| − | == Internetlänkar == | + | |

| + | == <b><span style="color:#931136">Internetlänkar</span></b> == | ||

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iYgG4LUqXks | http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iYgG4LUqXks | ||

| Rad 175: | Rad 373: | ||

| − | [[Matte:Copyrights|Copyright]] © | + | [[Matte:Copyrights|Copyright]] © 2010-2015 Math Online Sweden AB. All Rights Reserved. |

Versionen från 24 juni 2015 kl. 15.32

| <-- Till Polynom | Genomgång | Övningar |

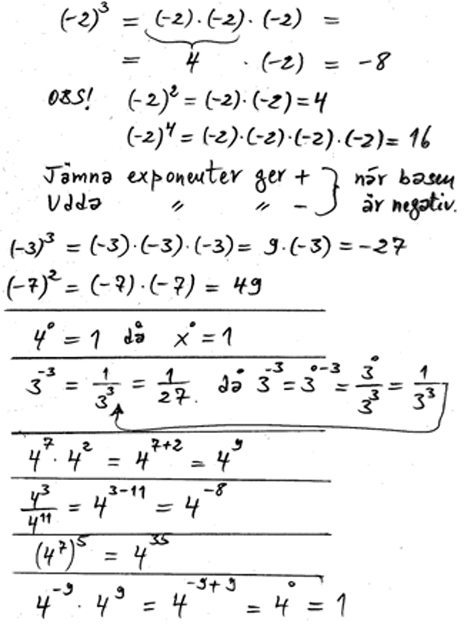

Vad är en potens?

\[ {\rm {\color{Red} {OBS!\quad Vanligt\,fel:}}} \quad\; 2\,^3 \; = \; 6 \]

\[ {\rm {\color{Red} {OBS!\quad Vanligt\,fel:}}} \quad\; 2\,^3 \; = \; 6 \]

\[ \qquad\quad\;\, {\rm Rätt:} \qquad\qquad\! 2\,^3 \; = \; 2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 \; = \; 4 \cdot 2 \; = \; 8 \]

Felet beror på att man blandar ihop två olika räkneoperationer: multiplikationen med upphöjt till.

Hjärnan associerar \( \, 2 \, \) och \( \, 3 \, \) blind till multiplikationstabellen vilket ger \( \, 6 \, \).

I själva verket betyder \( \, 2\,^{\color{Red} 3} \, \) inte \( \, 2 \cdot 3 \, \) utan \( \, \underbrace{2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2}_{{\color{Red} 3}\;\times} \, \) och är en:

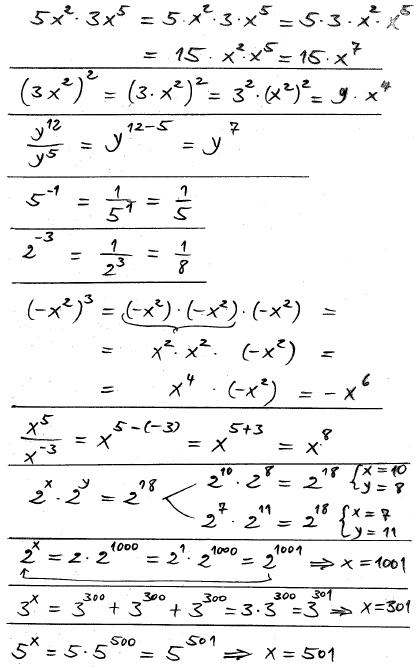

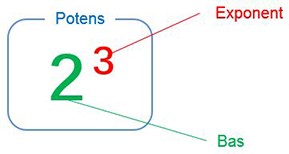

Potens

Upprepad multiplikation av \(2 \, \) med sig själv, \( \, {\color{Red} 3} \, \) gånger. |

|

\( \, 2\,^3 \, \) läses \( \, {\color{Red} 2} \) upphöjt till\( \, {\color{Red} 3} \, \) och kallas för potens. \( \, 2\, \) heter basen och \( \, 3 \, \) exponenten.

Exponenten \( \, {\color{Red} 3} \, \) är inget tal i vanlig bemärkelse utan endast en information om att \( \, 2 \, \) ska multipliceras \( \, {\color{Red} 3} \, \) gånger med sig själv (jfr. upprepad addition).

Exempel 1

Förenkla: \( \qquad \displaystyle{2\,^3 \cdot \; 2\,^5 \over 2\,^4} \)

Lösning: \( \qquad \displaystyle{{2\,^3 \cdot \; 2\,^5 \over 2\,^4} \, = \, {2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 \quad \cdot \quad 2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 \over 2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2} \, = \, {2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 \quad \cdot \quad 2 \cdot \cancel{2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2} \over \cancel{2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2}} \, = \, 2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 \, = \, 4 \cdot 4 \, = \, 16} \)

- OBS! Förenkla alltid först, räkna sedan!

Snabbare: \( \qquad\!\! \displaystyle{{2\,^3 \cdot \; 2\,^5 \over 2\,^4} \, = \, 2\,^{3\,+\,5\,-\,4} \, = \, 2\,^4 \, = \, 2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 \, = \, 4 \cdot 4 \, = \, 16} \)

För att förstå den snabbare lösningen se potenslagarna.

Potens med positiva heltalsexponenter

Potensen \( \, a\,^{\color{Red} x} \, \) kan, om exponenten \( \, {\color{Red} x} \, \) är ett positivt heltal och basen \( \, a \, \) ett tal \( \neq 0 \), definieras som

- Upprepad multiplikation av \( \, a \, \) med sig själv, \( \, {\color{Red} x} \, \) gånger:

- \( a\,^{\color{Red} x} = \underbrace{a \cdot a \cdot a \cdot \quad \ \cdots \quad \cdot a}_{{\color{Red} x}\;{\rm gånger}} \)

Exempel 2

Förenkla: \( \quad\;\; a\,^2 \, \cdot \, a\,^3 \)

Lösning:

- \( a\,^2 \cdot a\,^3 \; = \; \underbrace{a \cdot a}_{2\;\times} \; \cdot \; \underbrace{a \cdot a \cdot a}_{3\;\times} \; = \; \underbrace{a \cdot a \cdot a \cdot a \cdot a}_{{\color{Red} 5}\;\times} \; = \; a\,^{\color{Red} 5}\)

Snabbare:

- \( a\,^2 \cdot a\,^3 \; = \; a\,^{2\,+\,3} = \; a\,^{\color{Red} 5} \)

Den snabbare lösningen är ett exempel på den första potenslagen:

Potenslagarna

Följande lagar gäller för potenser där basen \( a\, \) är ett tal \( \neq 0 \), exponenterna \( \, x \, \) och \( \, y \, \) godtyckliga tal och \( m,\,n \) heltal (\( n\neq 0 \)):

Första potenslagen: \( \qquad\qquad\quad\;\, a^x \cdot a^y \; = \; a\,^{x \, + \, y} \qquad\qquad \)

Andra potenslagen: \( \qquad\qquad\qquad\quad \displaystyle {a^x \over a^y} \; = \; a\,^{x \, - \, y} \qquad\qquad \)

Tredje potenslagen: \( \qquad\qquad\qquad \displaystyle {(a^x)^y} \; = \; a\,^{x \, \cdot \, y} \qquad\qquad \)

Lagen om nollte potens: \( \qquad\qquad\qquad\! a\,^0 \; = \; 1 \qquad\qquad \)

Lagen om negativ exponent: \( \qquad\qquad a\,^{-x} \; = \; \displaystyle {1 \over a\,^x} \qquad\qquad \)

Lagen om rationell exponent: \( \qquad\qquad a^{m \over n} \; = \; \sqrt[n]{a^m} \qquad\qquad \)

Specialfall \(m=1\) (högre rötter): \( \qquad\quad\;\, a^{1 \over n} \; = \; \sqrt[n]{a} \qquad\qquad \)

Potens av en produkt: \( \qquad\qquad\;\;\, (a \cdot b)\,^x \; = \; a\,^x \cdot b\,^x \qquad\qquad \)

Potens av en kvot: \( \qquad\qquad\qquad \left(\displaystyle {a \over b}\right)^x \; = \; \displaystyle {a\,^x \over b\,^x} \qquad\qquad \)

För enkelhets skull definierades potensbegreppet inledningsvis endast för positiva heltalsexponenter \( \, x \, \) och \( \, y \). Men potenslagarna gäller även för negativa och rationella exponenter. I formuleringen "negativ exponent" antas \( \, x > 0 \).

Bevis(idéer) och exempel för några potenslagar

Påstående (Första potenslagen):

- \( a\,^x \cdot a\,^y \; = \; a\,^{x \, + \, y} \)

Bevisidé:

Påståendet kan bevisas genom att använda potensens definition:

- \( a\,^{\color{Red} x} \cdot a\,^{\color{Red} y} \; = \; \underbrace{a \cdot a \cdot \; \ \cdots \; \cdot a}_{{\color{Red} x}\;\times} \; \cdot \; \underbrace{a \cdot a \cdot \; \ \cdots \; \cdot a}_{{\color{Red} y}\;\times} \; = \; \underbrace{a \cdot a \cdot \; \ \cdots \; \cdot a}_{{\color{Red} {x\,+\,y}}\;\times} \; = \; a\,^{{\color{Red} {x\,+\,y}}} \)

Påstående (Andra potenslagen):

- \( \displaystyle {a\,^x \over a\,^y} \; = \; a\,^{x \, - \, y} \)

Exempel 3

- \( \displaystyle {a\,^{\color{Red} 5} \over a\,^{\color{Red} 3}} \; = \; {a \cdot a \cdot a \cdot a \cdot a \; \over \; a \cdot a \cdot a} \; = \; {a \cdot a \cdot \cancel{a \cdot a \cdot a} \; \over \; \cancel{a \cdot a \cdot a}} \; = \; a \cdot a \; = \; a\,^2 \)

Snabbare med andra potenslagen:

- \( \displaystyle {a\,^{\color{Red} 5} \over a\,^{\color{Red} 3}} \; = \; a\,^{{\color{Red} {5\,-\,3}}} \; = \; a\,^2 \)

Påstående (Lagen om nollte potens):

- \( a^0 \; = \; 1 \)

Bevis:

Påståendet kan bevisas genom att använda andra potenslagen:

- \( \displaystyle{a^x \over a^x} \; = \; a^{x-x} \; = \; a^0 \)

Å andra sidan vet vi att ett bråk med samma täljare som nämnare har värdet \( \, 1 \):

- \( \displaystyle{a^x \over a^x} \; = \; 1 \)

Av raderna ovan följer påståendet:

- \( a^0 \; = \; 1 \)

Potenser med negativa exponenter

Påstående (Lagen om negativ exponent, \( \, x > 0 \)):

- \( a^{-x} = \displaystyle{1 \over a^x} \)

Bevis:

Påståendet kan bevisas genom att använda den ovan bevisade lagen om nollte potensen (baklänges) samt andra potenslagen:

- \( \displaystyle{1 \over a^x} \; = \; \displaystyle{a^0 \over a^x} \; = \; a^{0-x} \; = \; a^{-x} \)

Vi får påståendet, fast baklänges.

Exempel på potenser med negativa exponenter

- \( \displaystyle{a^{-1} \, = \, {1 \over a^1} \, = \, {1 \over a}} \)

- \( \displaystyle{a^{-2} \, = \, {1 \over a^2} \, = \, {1 \over a \cdot a}} \)

- \( \displaystyle{a^{-3} \, = \, {1 \over a^3} \, = \, {1 \over a \cdot a \cdot a}} \)

Att potenser med negativa exponenter är en naturlig fortsättning på potenser med positiva exponenter med nollte potensen däremellan illustrerar följande exempel:

Varför är \( \; 5\,^0 \, = \, 1 \; \)?

- \[ \;\; 5^4 \; = \; {\color{Red} 1} \cdot 5 \cdot 5 \cdot 5 \cdot 5 \]

- \[ \;\; 5^3 \; = \; {\color{Red} 1} \cdot 5 \cdot 5 \cdot 5 \]

- \[ \;\; 5^2 \; = \; {\color{Red} 1} \cdot 5 \cdot 5 \]

- \[ \;\; 5^1 \; = \; {\color{Red} 1} \cdot 5 \]

- \[ \;\; {\color{Red} {5^0 \; = \; 1}} \]

- \[ \;\; 5^{-1} \; = \; \displaystyle{{\color{Red} 1} \over 5} \]

- \[ \;\; 5^{-2} \; = \; \displaystyle{{\color{Red} 1} \over 5 \cdot 5} \]

- \[ \;\; 5^{-3} \; = \; \displaystyle{{\color{Red} 1} \over 5 \cdot 5 \cdot 5} \]

- \[ \;\; 5^{-4} \; = \; \displaystyle{{\color{Red} 1} \over 5 \cdot 5 \cdot 5 \cdot 5 } \]

Att \( \; {\color{Red} 1} \)-orna följer med hela tiden beror på att multiplikationens enhet är \( \, {\color{Red} 1} \), dvs \( \, a \cdot {\color{Red} 1} \, = \, a \). Därför blir endast \( \, {\color{Red} 1} \, \) kvar, när vi kommer till \( \, {\color{Red} {5^0}} \, \) då alla \( \, 5\)-or har försvunnit.

Jämför med:

Varför är \( \; 5 \cdot 0 \, = \, 0 \; \)?

- \[ \;\; 5 \cdot 4 \; = \; {\color{Red} 0} + 5 + 5 + 5 + 5 \]

- \[ \;\; 5 \cdot 3 \; = \; {\color{Red} 0} + 5 + 5 + 5 \]

- \[ \;\; 5 \cdot 2 \; = \; {\color{Red} 0} + 5 + 5 \]

- \[ \;\; 5 \cdot 1 \; = \; {\color{Red} 0} + 5 \]

- \[ \;\; {\color{Red} {5 \cdot 0 \; = \; 0}} \]

- \[ \;\; 5 \cdot (-1) \; = \; {\color{Red} 0} - 5 \]

- \[ \;\; 5 \cdot (-2) \; = \; {\color{Red} 0} - 5 - 5 \]

- \[ \;\; 5 \cdot (-3) \; = \; {\color{Red} 0} - 5 - 5 - 5 \]

- \[ \;\; 5 \cdot (-4) \; = \; {\color{Red} 0} - 5 - 5 - 5 - 5 \]

Att \( \; {\color{Red} 0} \)-orna följer med hela tiden beror på att additionens enhet är \( \, {\color{Red} 0} \), dvs \( \, a + {\color{Red} 0} \, = \, a \). Därför blir endast \( \, {\color{Red} 0} \, \) kvar, när vi kommer till \( \, {\color{Red} {5 \cdot 0}} \, \) då alla \( \, 5\)-or har försvunnit.

Potenser med rationella exponenter

Potenser med exponenter som är rationella tal (bråktal) kan användas för att beräkna (högre) rötter.

Påstående (högre rötter):

- \( a^{1 \over n} \; = \; \sqrt[n]{a} \; \) \( , \qquad n\neq 0 \)

Bevisidé:

Vi tar specialfallet \( n=3 \), multiplicerar \( a \)\(^{1 \over 3} \) tre gånger med sig själv och använder potenslagen om produkt av potenser med samma bas:

- \( \displaystyle a^{1 \over 3} \cdot a^{1 \over 3} \cdot a^{1 \over 3} \; = \; a^{{1 \over 3} + {1 \over 3} + {1 \over 3}} \; = \; a^{3 \over 3} \; = \; a^1 \; = \; a \)

Definitionen för 3:e roten ur \( a \) är:

\( \qquad\quad \displaystyle \sqrt[3]{a} \; = \; \) Tal som 3 gånger multiplicerat med sig själv ger \( a \).

Men enligt ovan är det tal som 3 gånger med sig själv ger \( a \), just \( a \) \(^{1 \over 3} \). Alltså måste detta tal vara lika med 3:e roten ur \( a \):

- \( \displaystyle a^{1 \over 3} \; = \; \sqrt[3]{a} \)

Denna bevisidé kan vidareutvecklas till det allmänna fallet för alla heltal \( m\, \) och \( n\neq 0 \, \) (Lagen om rationell exponent):

- \( a^{m \over n} \; = \; \sqrt[n]{a^m} \)

Potensekvationer

Anta i fortsättningen att \( \, x \, \) är en okänd variabel och \( b\, \) och \( c\, \) givna konstanter \( \neq 0 \) .

- Funktioner av typ \( y = x^3\, \) kallas potensfunktioner, generellt \( \; y = c \cdot x^b\, \).

- Ekvationer av typ \( x^3\, = 8 \) kallas potensekvationer, generellt \( \; x^b\, = c \).

I potensfunktioner och -ekvationer förekommer \( \, x \, \) i basen. Potensekvationer löses genom rotdragning. För t.ex. potensekvationen \( x^3\, = 8 \) finns det två olika sätt att beskriva lösningen via rotdragning:

- \[\begin{align} x^3 & = 8 \qquad & | \; \sqrt[3]{\;\;} \\ \sqrt[3]{x^3} & = \sqrt[3]{8} \\ x & = 2 \\ \end{align}\]

Alternativt (med rationell exponent):

- \[\begin{align} x^3 & = 8 \qquad & | \; (\;\;\;)^{1 \over 3} \; \text{samma som} \; \sqrt[3]{\;\;} \\ (x^3)^{1 \over 3} & = 8^{1 \over 3} \\ x^{3\cdot{1 \over 3}} & = 8^{1 \over 3} \\ x & = 2 \\ \end{align}\]

Det alternativa sättet att lösa ekvationen ovan visar att rötter även kan uppfattas och skrivas som potenser med rationella exponenter.

Blandade exempel

Internetlänkar

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iYgG4LUqXks

http://www.webbmatte.se/gym/arabiska/2/2_8_4sv.html

http://www.webbmatte.se/gym/arabiska/2/2_8_3sv.html

http://wiki.math.se/wikis/forberedandematte1/index.php/1.3_%C3%96vningar

Copyright © 2010-2015 Math Online Sweden AB. All Rights Reserved.